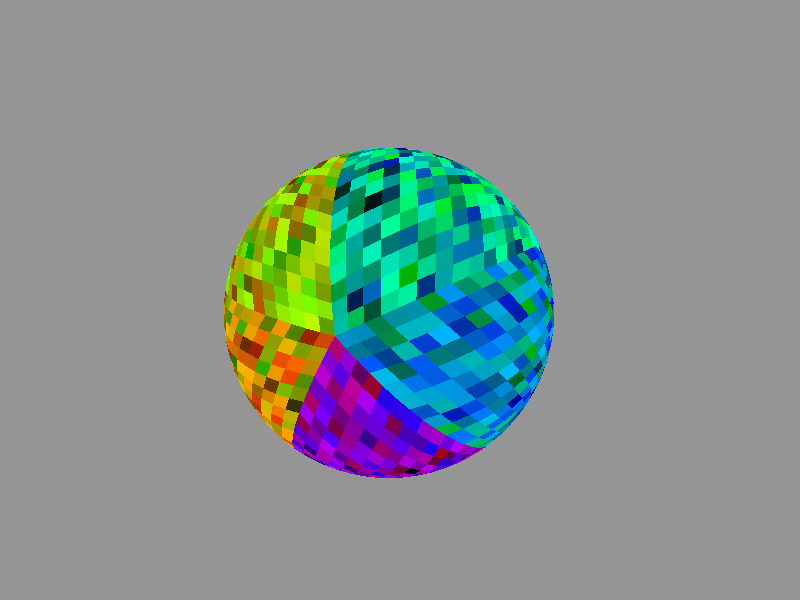

PlanetKit is my new side project combining Rust, graphics, and an as yet vaguely defined idea. (More on that last bit later.) I’m planning to use it as a test bed for a bunch of semi-related experiments and maybe even eventually build a playable game on top of it. Right now it’s little more than a graphical “Hello, world!”:

You might then reasonably ask why am I blogging about it now? I have a few reasons:

-

I’ve been intending for a while to try writing about something as I work on it—from the start—to see how it changes the way I work.

I recognise the most likely outcome is that very few people will even notice this project, and that’s fine. My hypothesis is that writing about it publicly as I go will influence how I work on it more generally, so while it would be nice to attract some interest, it’s far from being essential to the experiment.

-

In total unabashed contradiction to the huge caveat in my first reason, I’ve been rolling around in my head for a while a stupidly ambitious idea for a community-oriented game development project.

-

All the reasons Michael Gattozzi discussed in his post on blogging about Rust. If you haven’t yet read it, I highly recommend doing so!

Where are we now?

Here’s what I’ve done so far:

-

Learned how to use Piston and GFX, largely ripping off code from the Piston project’s cube example and filling in the gaps with this article on GFX’s programming model.

-

Played around with the simplex noise provided by noise-rs. I’ve actually mostly removed that code now, but I’m going to drop it back in shortly as the basis for procedurally generating planet surfaces and interiors.

-

Dropped in a colorful icosahedron. Learned a tiny bit of GLSL, mostly through trial and error. I should probably read a book on this or something soon.

-

Tried to build using Emscripten. It doesn’t work yet (see below) but I’m super enthusiastic about where this is headed. If I can get an Emscripten build working, then I’ll make it part of my process to always have a recent snapshot of all PlanetKit runnables hosted somewhere.

-

Tiled the surface of the icosahedron with cells. You can see these are currently rendered as quads, but they will eventually be mostly hexagons, plus the obligatory 12 pentagons.

Here’s another gratuitous screenshot of what the planet looks like from the inside—mostly just to break up this wall of text.

You can get the latest code from the PlanetKit GitHub repository. Whenever I find time to work on this thing, I’ll be pushing everything up there as I go.

If you want to try running it, clone the repo and…

cargo run

That should do it. If it doesn’t work, please file a bug.

Challenges so far

It took me a while to figure out how to use GFX. I still don’t really understand how to use it effectively. Specifically, I’m not sure how I should approach dynamically creating, destroying, and rendering lots of heterogeneous objects in my scene. I imagine I’m going to have to bite the bullet on this pretty soon. I’ll write about my experience.

While Emscripten support in Rust looks really promising, it doesn’t seem to actually work at the moment. I got a CLI-only “Hello, world!” app building and running in Chrome, but ran into this bug when I tried to build PlanetKit.

What’s next?

Next up is rendering the cells as hexagonal prisms, and taking a first stab at terrain by throwing some simplex noise at a voxmap.

Ugh, get to the point. What’s this idea?

Oh, right. That. The idea I mentioned earlier is actually a mishmash of several different ideas that don’t seem to be entirely incompatible. I haven’t yet figured out how to combine them into a coherent plan or philosophy, but in the spirit of releasing early, I’ll put some bullet points out there for comment:

-

Draw heavy inspiration from the way Mozilla runs its communities, and try to apply it to a game technology project. Rust’s code of conduct in particular appeals to me, as does their collaborative approach to planning and reviewing changes. Encourage people to file issues for everything: bugs, feature requests, questions about why the project exists, etc.

-

Release early (done), release often. Always ask whether a given unit of work could be broken down into smaller units that could be discussed, built, and delivered separately. The goal here is to maximise interaction and transfer of knowledge, and drastically lower the barrier to entry for contributors by carving off small, well-defined tasks for other people to do wherever possible.

-

Make documentation as important as running code. If I can’t take an arbitrary struct or function and understand where it fits into the puzzle—at very least a link off to some other page/file that will provide some context—then that’s a bug. The goal here is to minimise the barrier to entry, and to use the code as a teaching tool.

-

Instead of trying to rally people around a single game that must please everyone, focus on pushing shareable tech down as far as it can go, and encourage everyone involved to have their own game project, even if they’re also involved in another.

Wait, what? Everyone would have their own game project? Who has the time for that, you crazy person?

I wrote way more than I intended to on this point, so I’ve moved most of it to a separate draft post for later. The short version is this: the simple case of “I want to start a game where people jump around on a planet” shouldn’t need to be more than 100 lines of code all told. And then as I slowly develop ideas about how this game should actually work, I should be able to gradually specialise components—I shouldn’t need to throw the whole thing away to rebuild the “real” way.

When I realise that having the main character flying is going to be central to my game, I’d swap out the ExampleComplexHuman I started with for a custom implementation that pieces together many of the same bits that comprise ExampleComplexHuman but can also take off, fly, land, etc., and then maybe if I’m in a really good mood, I’ll contribute these behaviours back for other people to use. Or I might just decide that I want to remove some behaviour from ExampleComplexHuman, and follow much the same process to achieve it.

The key design decision here would be to offer for every abstract concept both a trivial implementation (the human is a grey cuboid that can move around, jump, and fall) and at least one sample complex implementation (full skeletal animation, ability to hold both either separate light objects in each hand, or one heavy object with both hands). The goal here is to push large parts of these more complex implementations down into reusable libraries, so that their uses in specific games would then look more like configuration of visual appearance, physical characteristics like mass and max speed, and any custom behaviours that are totally specific to that game.

This doesn’t completely explain the model I’m going for, so I will make a separate post about this. With code.

Wrapping up

This initial post has ended up rather nebulous. Subsequent posts will focus on specific details, and will include code, diagrams, and compiler output. I promise.