PlanetKit is a project aimed at creating a toolkit for making interactive virtual worlds. I’m writing it in the Rust programming language, which I’m finding delightful to work with, and a great fit for the task.

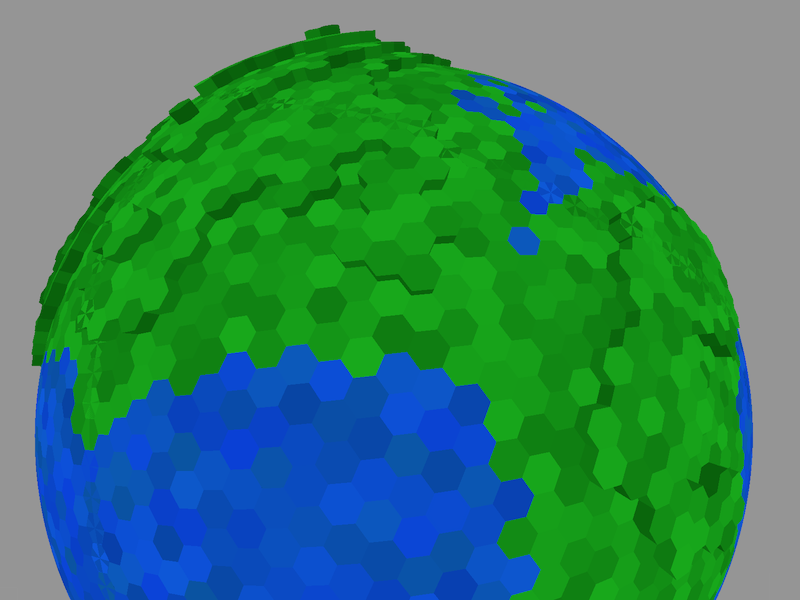

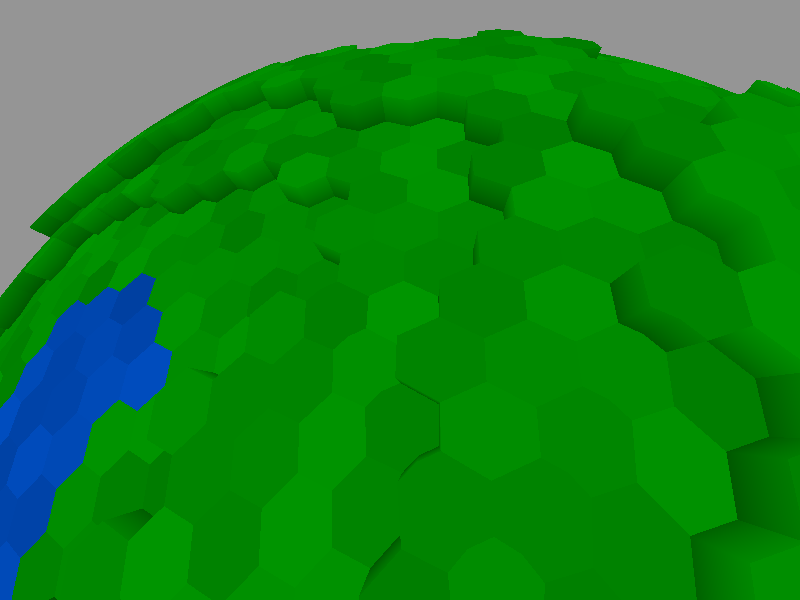

Last week we turned our lumpy blob into world of hexagonal prism voxels. That ended up looking like this:

But there were a couple of really obvious problems.

Accidental rendering of back-faces

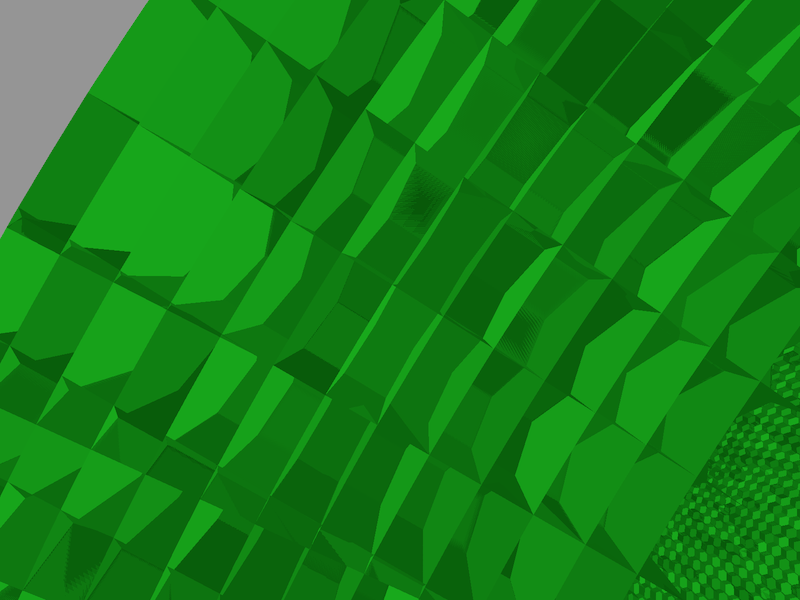

First and more boring of those was how much redundant geometry I was rendering. If you peek inside the globe, you’d see something like this:

I noticed from my swimming around inside the globe that I could see the tops of the hexagonal prisms from underneath. That’s not great. That means that most of the time there will be a bunch of triangles being drawn to the screen that I never actually intend to be seen. So the first easy win there was to enable back-face culling. This is how I was initializing my Gfx-rs Pipeline State Object before:

let pso = factory.create_pipeline_simple(

Shaders::new()

.set(GLSL::V1_50, include_str!("shaders/copypasta_150.glslv"))

.get(glsl).unwrap().as_bytes(),

Shaders::new()

.set(GLSL::V1_50, include_str!("shaders/copypasta_150.glslf"))

.get(glsl).unwrap().as_bytes(),It’s nice to have a simpler helper like create_pipeline_simple, and I’m surprised to have “outgrown” it so quickly. Fortunately the not-quite-as-simple PSO set-up isn’t much more complicated:

let mut vs = Shaders::new();

let vs_bytes = vs

.set(GLSL::V1_50, include_str!("shaders/copypasta_150.glslv"))

.get(glsl).unwrap().as_bytes();

let mut ps = Shaders::new();

let ps_bytes = ps

.set(GLSL::V1_50, include_str!("shaders/copypasta_150.glslf"))

.get(glsl).unwrap().as_bytes();

let shader_set = factory.create_shader_set(vs_bytes, ps_bytes).unwrap();

let pso = factory.create_pipeline_state(

&shader_set,

Primitive::TriangleList,

Rasterizer::new_fill().with_cull_back(),

pipe::new()

).unwrap();Notice the call to with_cull_back in the replacement code. Yay, no more pointless back-faces.

Unreachable voxels

The next step was to cull all the geometry for any voxels that are obviously never going to be visible. I initially started trying to write out something clever that would properly take into account voxels on the edge of chunk boundaries, and do it efficiently by making sure I always had cached copies of all the voxels from neighbouring chunks that I—no! Stop! Make it work, make it right, make it fast. In that order.

I might change my mind about the fundamentals of the way this voxmap is stored three times before this level of optimisation is relevant. So instead I dealt with the most egregious waste of triangles within the bulk of chunks with the following simple algorithm:

- If the voxel is on the edge of a chunk, draw it.

- Otherwise, if any of its neighboring voxels are made of air, then maybe it could be seen, so draw it.

- Otherwise, don’t draw it.

This eliminated the vast majority of wasted geometry in my globe. I haven’t bothered getting numbers to back this up yet, but I was able to crank the resolution of the world up a lot after doing this before it started slowing down again.

Overlapping voxels on chunk boundaries

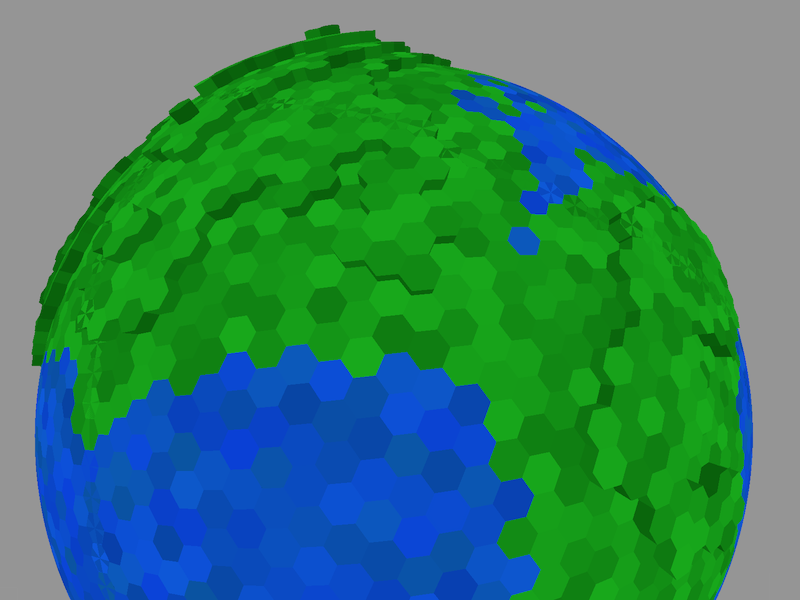

Next up I needed to deal with overlapping voxels at chunk boundaries. Taking another quick look at the problem in the picture above:

How did I say I was going to solve that?

Whilst one chunk will eventually have to own the data for each boundary cell (otherwise how will I know what is the authoritative state of the cell?), I’m intending that a chunk will render only the part of the boundary cells that fall within the bounding quad for that chunk. […]:

Well, that I did! Here’s an expanded version of the diagram from the last post, showing a cross section of the smallest possible chunk that includes all the 9 partial hexagon shapes we’ll need:

● y

x |`~◌ ↘

↓ ◌ `~◌

| ◌ `~●

◌ ◌ / `~◌

| ◌ / ◌ `~◌

●-----● ◌ `~◌

| ◌ \ ◌ ◌ `~◌

◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌ `~◌

| ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ `~●

◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌ ◌ / `~◌

| ◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌ / ◌ `~◌

◌ ◌ ●-----◌-----● ◌ `~●

| ◌ ◌ / ◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌ |

◌ ◌ / ◌ ◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌

| ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ |

◌ ◌ / ◌ ◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌

| ◌ / ◌ ◌ ◌ \ ◌ |

●-----● ◌ ◌ ◌ ●-----●

| ◌ \ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ / ◌ |

◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌ ◌ / ◌ ◌

| ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ |

◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌ ◌ / ◌ ◌

| ◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌ / ◌ ◌ |

● ◌ ●-----◌-----● ◌ ◌

`~◌ ◌ / ◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌ |

`~◌ / ◌ ◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌

`~● ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ |

`~◌ ◌ ◌ \ ◌ ◌

`~◌ ◌ ◌ \ ◌ |

`~◌ ◌ ●-----●

`~◌ ◌ / ◌ |

`~◌ / ◌ ◌

`~● ◌ |

`~◌ ◌

`~◌ |

`~●The filled circles represent vertices that will be used in the geometry for a given shape. Note that voxel centres are included explicitly only where needed, unlike before where I was including them indiscriminitely in every triangle, because it hadn’t yet crossed my mind to do anything different.

Dropping in a table of references to these vertices, and a tiny bit of logic around what voxel in a chunk should be drawn as what shapes gives us this:

Hurrah! No more weird overlaps!

But there’s still a line down the middle—what’s the deal with that? That’s because there are actually two completely independent voxels at each point on the boundary, one of which belongs to each chunk. I didn’t yet have any way of deciding which chunk holds the source of truth for a given voxel.

Brief detour: picking the wrong optimisation

An icosahedron can be flattened into a net comprising 20 triangles:

● ● ● ● ●

/ \ / \ / \ / \ / \

/ \ / \ / \ / \ / \

●-----●-----●-----●-----●-----●

\ / \ / \ / \ / \ / \

\ / \ / \ / \ / \ / \

●-----●-----●-----●-----●-----●

\ / \ / \ / \ / \ /

\ / \ / \ / \ / \ /

● ● ● ● ●We can then, for the sake of having a data structure that is square in memory (we like those), group this into 5 “root quads”, each of which comprises a strip of four triangles running all the way from the north pole of the globe down to the south. These root quads are twice as long (y-axis) as they are wide (x-axis).

Highlighting the first quad to illustrate:

● ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌

/·\ / \ / \ / \ / \

/···\ / \ / \ / \ / \

● - - ●-----◌-----◌-----◌-----◌

\···/·\ / \ / \ / \ / \

\·/···\ / \ / \ / \ / \

● - - ●-----◌-----◌-----◌-----◌

\···/ \ / \ / \ / \ /

\·/ \ / \ / \ / \ /

● ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌But I originally broke my world up into 10 root quads. My reasoning was that having 10 root quads is somehow “neater”, because then they have the same resolution in x and y directions. In retrospect that is almost entirely nonsense. Even if that property is nice to have for some purposes, it’s only really relevant when we get down to dealing with individual chunks, which can still easily be square either way.

And the hugely important thing that I hadn’t considered until now is that having 10 root quads massively complicates any logic involving the interface between quads: instead of having only one type of root quad, the distinction between northern and southern hemisphere quads introduced by having 10 quads means each would have their own properties, and the number of kinds of interfaces between them multiply out into a mess.

Yuck.

Who owns the border?

Now that I’ve simplified my world down to having 5 long root quads, here’s what the ownership of voxels looks like, with filled circles representing voxels owned by the root, and empty circles representing voxels owned by an adjacent root:

Root 0 Roots 1, 2, 3 Root 4

------ ------------- ------

● ◌ ◌

◌ ● ◌ ● ◌ ●

◌ ● ● ◌ ● ● ◌ ● ●

◌ ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ●

◌ ● ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ●

◌ ● ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ●

◌ ● ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ●

◌ ● ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ●

◌ ● ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ●

◌ ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ● ◌ ● ● ●

◌ ● ● ◌ ● ● ◌ ● ●

◌ ● ◌ ● ◌ ●

◌ ◌ ●Notice how adacent roots neatly slot into each other’s non-owned cells when wrapped around the globe.

Also note the special cases for north and south poles; they don’t fit neatly into the general pattern. There’s no way to make them fit neatly, so unfortunately they’ll just have to be dealt with as a special case in any algorithms that care about that sort of thing. This is just one of those things, like tiling a sphere with billions of hexagons always also requiring 12 pentagons to tie the whole thing together.

Breaking those roots down into chunks works basically the same: each chunk owns two of its edges, and accepts the values from its neighbours as authoritative for the other two. At the moment I’m implementing this by simply looping over all voxels in all chunks after all chunks have been created, and finding and copying the source of truth for any voxel not owned by the chunk I’m currently examining. It’s brain-dead (I’m not even restricting the search to border voxels) but it doesn’t increase the complexity class of the whole thing, and it’s far from being a bottleneck at the moment. That’ll be an optimisation to care about once I’m dynamically updating the world.

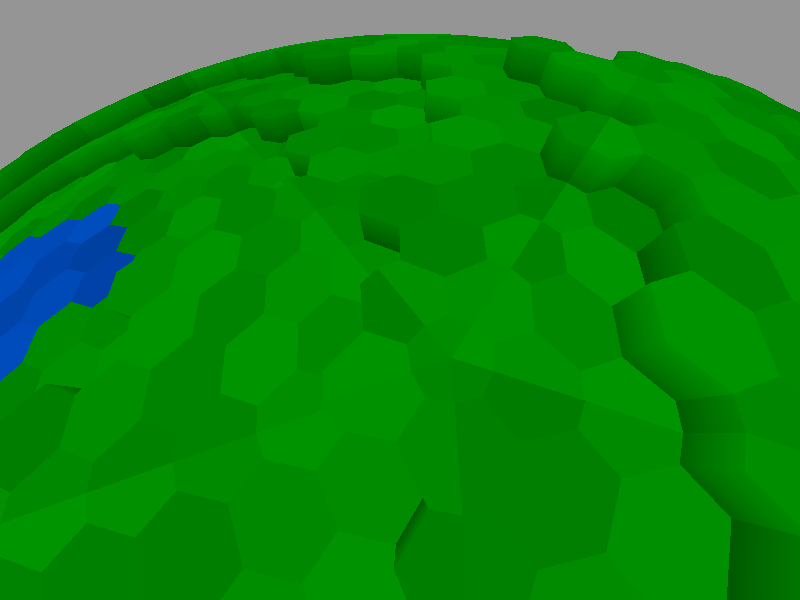

And here’s what it looks like now:

Aw, yiss!

What’s next?

Next up I’m going to start building a simple game on top of this. I’m expecting progress to be very slow initially, because this also means I need to:

- Spend some time playing with SPECS, which I’ve decided is probably exactly what I need for managing entities and their components; and

- Figure out how I’m actually supposed to use Pipline State Objects in practice, when I have multiple kinds of things that I want to draw. Should I be defining them sparingly and trying to use the same shaders for as much as possible, or is the intended use closer to making a new PSO for every kind of entity/thing I’ll be drawing? I’ve never done anything interesting with a video card before, so this is just a necessary learning curve.

Stay tuned for more hexagonal fun!

As always, the source for everything I’m talking about here is up in the planetkit repository on GitHub.