UPDATE: I accidentally published this with the same date as the previous post. I’ve corrected the date above to 2016-12-19, but I’m leaving the incorrect date in the URL to preserve permalinks.

PlanetKit is a project aimed at creating a toolkit for making interactive virtual worlds. I’m writing it in the Rust programming language, which I’m finding delightful to work with, and a great fit for the task.

It’s been nearly a month since I last posted here, so I’m going to drop the pretense of it being a weekly blog. The main reason it’s been so long is that I’ve been chipping away at a few unglamorous bits and pieces. So, alas, no pretty screenshots this week.

What have I been up to?

A lot of my commits recently have been boring housekeeping:

- Split draw code out into its own module.

- Un-bundle meshes from Pipeline State Objects so I can share the PSOs across multiple meshes. This is more efficient, because it avoids loading a new shader program if multiple meshes could re-use the same program.

- Emit a separate mesh per chunk of the world in preparation for dynamically loading/unloading chunks.

- Turn PlanetKit into a library crate. (I haven’t published it on crates.io yet.)

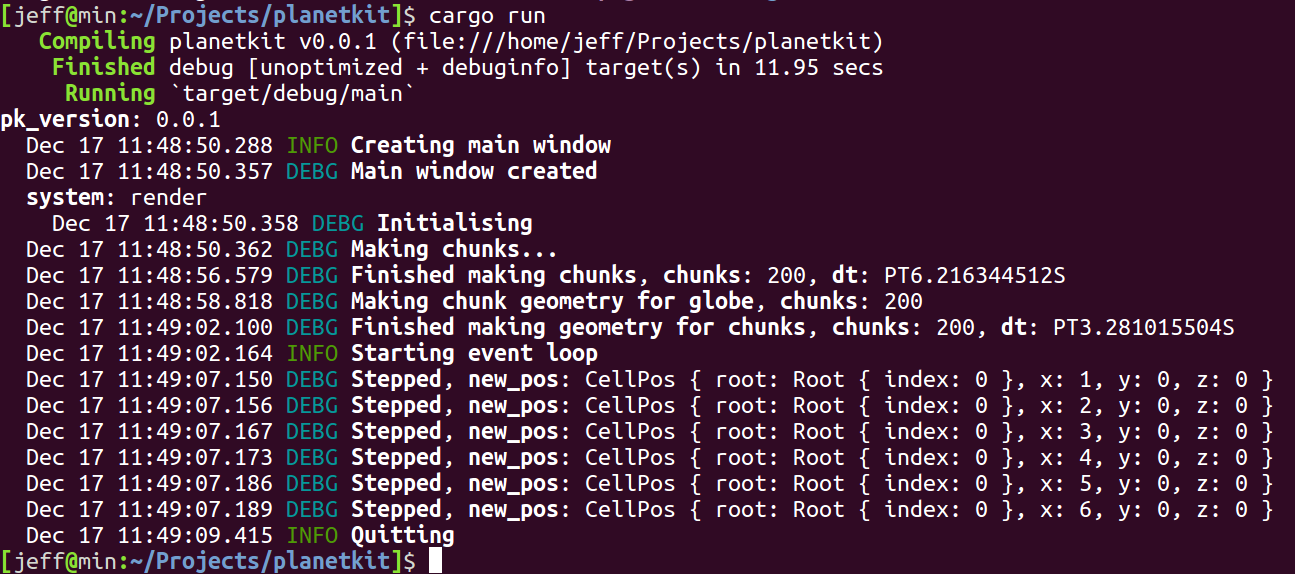

- Add some structured logging using the

slogcrate. Zbigniew Siciarz recently wrote about slog in his “24 days of Rust” series.

The more interesting changes in the mix were…

Keep the simple case simple

One of my core philosophies going into this project has been that the simple case should be simple. Here’s the main.rs for my example:

extern crate planetkit as pk;

fn main() {

let (mut app, mut window) = pk::simple::new();

app.run(&mut window);

}The second part of that philosophy is that moving from the simple case to a more complex case should not involve rewriting everything from scratch – i.e. there is not a “quick and dirty way” and a “right way”, each of which has nothing to do with the other. So obviously the above doesn’t really prove anything yet. But with this token effort to keeping the simplest example extremely terse, I’m making a commitment to making it easy to start with something simple, and then slowly mutate it into whatever game you’re actually trying to build, much in the spirit of video game modding scene.

This will manifest in the first couple of example games I build on top of PlanetKit. In each case I will be constantly trying to push things down into lower layers such that the code describes only the things that are legitimately unique to that game.

Expect more on this as I figure out what the API should look like for things like ExampleSimpleThing, ExampleComplexThing, ExamplePluggableThing, etc.

Moving to an Entity-Component System, and learning from Yasteroids

As promised, I’ve ported what I’ve done so far to use the specs ECS! Right now, I only have my rendering system and the basics of input handling hooked up, but everything else I build will be based on that start.

I was fortunate to stumble upon Yasteroids, which also uses both gfx and specs. So I had the great benefit of seeing how kvark approached the combination.

The first trick I lifted from Yasteroids was to have a pair of channels for passing around graphics command encoders between the thread owning the graphics device, and the render system (scheduled on some thread from a pool) responsible for generating the graphics commands for each frame. By having two encoders in flight at all times, it means that both the render system and the main thread always have an encoder available that they can do something meaningful with. The render system can be populating one command buffer while the main thread is flushing commands to the video card from the other. In this way it’s kind of like conventional double buffering but for command buffers instead of pixmap buffers.

The other pattern I stole is to interpret the meaning of user input outside of my systems, and then shovel that down a channel into a control system which doesn’t know anything about input devices. Instead, it’s only concerned with user actions like “begin moving forward”, which it then applies to any user-controllable game entities. This is a good place to split the concerns, because it means that my game systems could easily be switched to be driven by, e.g., a replay file instead of live user input.

Both of these concepts may seem pretty simple, and I suppose they are, but seeing a real example of how someone put those ideas together in practice has helped me to develop an intuitive feel for what might be a good way to approach other problems using an Entity Component System–which really helps, having never used one before! I think the hump it got me over was that of thinking I understood the concepts, but having enough doubt remaining that I’d still second-guess every idea that I tried to layer on top of that.

Movement!

I’ve made a token start on a component type for all entities that exist in and move between cells on a globe grid. I’m calling this a CellDweller. I hope the name’s similarity to a certain alternative metal project doesn’t create confusion.

This will be a little bit fiddly, because it means the next step is to figure out how to properly adjust the orientation of a CellDweller as it moves between different root quads. Recall the layout of said quads, considering in particular the three highlighted vertices:

● ● ◌ ◌ ◌

/ \ / \ / \ / \ / \

/ \ / \ / \ / \ / \

◌ ● ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌

\ \ \ \ \ \

\ \ \ \ \ \

◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌

\ / \ / \ / \ / \ /

\ / \ / \ / \ / \ /

◌ ◌ ◌ ◌ ◌Notice that the two highlighted vertices at the top are actually the same one (both are the north pole) once the net is folded into a sphere. So looking down the line in the positive y-direction in the first triangle is equivalent to looking down the line in the positive x-direction in the second.

What might be less clear from this diagram is that as you move from one quad to the next, the change in orientation depends not just on which pair of quads you are moving between, but also where in the quad you moved from.

I recognise that this is a little bit vague at this point, but this will become clear soon; my next post is almost definitely going to focus exclusively on CellDweller movement.

What’s next?

Next up I’m going to start building a simple game on top of this. Yes, that’s what I said last post. I also said it’d take a little while to get started, because of the need to explore a few things. Well, I’ve explored them, now, so it’s time to get cracking.

As I mentioned above, the first part of this is to figure out how my character needs to move on the voxel grid. Expect my next post to be almost entirely about that.

Stay tuned for more hexagonal fun!

As always, the source for everything I’m talking about here is up in the planetkit repository on GitHub.